from: Maps

ANONYMOUS [Nicolas de Finiels?] Plano de una parte de la Prov.a de la Luisiana; ... 1803

ANONYMOUS [Nicolas de Finiels?] Plano de una parte de la Prov.a de la Luisiana; ... 1803

Couldn't load pickup availability

Anonymous [Nicolas de Finiels?]

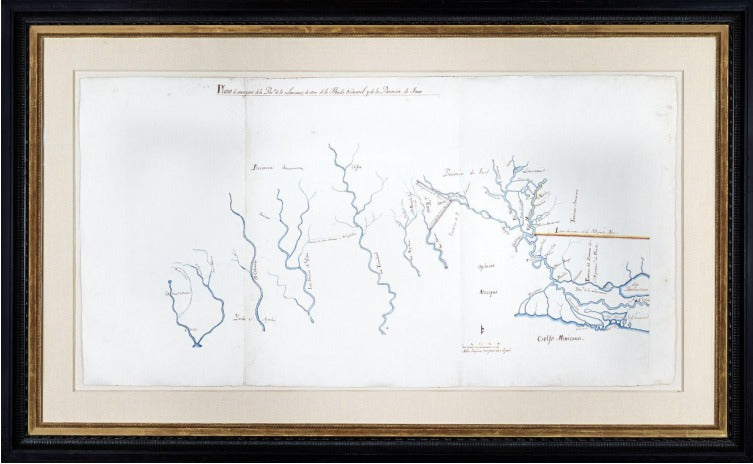

Plano de Una Parte de la Provincia de la Luisiana y de Otra de la Florida Occidental y de la Provincia de Texas [Map of a part of the Province of Louisiana and the other of West Florida and the Province of Texas]

Ink and watercolor wash on paper. Two sheets joined, float mounted and framed

watermarked "Whatman 1794" and with their fleur-de-lis

C. 1803-1806

Sheet size: 214/8 x 412/8 inches; Frame size: 32 3/4 x 51 3/4 inches

The Louisiana Purchase left confusion on many borders, including those of Texas, Louisiana, West Florida and the Mississippi Territory as displayed in this unique manuscript map.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 gave the new United States tall of Britain’s territory below Canada west of the Allegheny Mountains and east of the Mississippi, other than West Florida and East Florida. It was apparent to the new nation’s leaders that free transit of the Mississippi River through New Orleans to the Gulf of Mexico was of critical importance for the future of its western lands. In 1795 the Treaty of San Lorenzo (or Pinckney’s Treaty) with Spain gave Americans the right to deposit goods duty free in New Orleans for transit up and down the river, renewable every three years. The treaty also fixed the southern boundary between the United States and West Florida at the 31st Parallel. This finally resolved Spanish claims that extended as far north as Natchez.

In 1800 Napoleon persuaded Spain to the retrocession of Louisiana to France under the treaty of 1762. The parties kept the transfer secret, and Spain continued to administer the territory. When President Thomas Jefferson learned of the transfer, he feared that France would not honor the right of deposit for American goods. He instructed his envoy in Paris to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans from France, or in the alternative to obtain a permanent right of deposit there. No such deal was reached.

In 1802 the Spanish themselves rescinded the right of deposit, blaming the closure on behavior by the “Kaintucks.” This caused a political crisis in the United States as goods from the western territories could not be shipped through the city. Jefferson sent James Monroe to Paris to renew his offer to buy New Orleans. Short of funds to pursue his pacification of Dominica, Napoleon offered to sell all of Louisiana to the United States. Jefferson agreed, and the purchase was consummated in two stages in 1803 and 1804.

The Louisiana Purchase was the largest single land acquisition in the nation’s history, but the actual territory being conveyed was not clearly described in any agreement or treaty.Thepurchase treaty itself conveyed Louisiana to the United States “with the same extent that it now has in the hands of Spain, and that it had when France possessed it, and as it should be after the treaties subsequently entered into between Spain and other states.” Since the treaty that transferred it from France to Spain did not define the boundaries of Louisiana, this left the matter ambiguous. The reference to subsequent treaties by Spain added a further ambiguity. Napoleon has been famously quoted as saying had the matter not been ambiguous, he would have made it so, in order to avoid a conflict with Spain. In any event, the ambiguity had repercussions, both immediately and in the decades to follow.

One immediate point of conflict was at the intersection of Louisiana with West Florida, Texas and the United States’ Mississippi Territory. The United States argued that West Florida had originally been part of French Louisiana, and therefore it was conveyed to France and then to the United States as part of the purchase. A similar claim was made as to Texas, based on the historical disagreement between Spain and France as to the western boundary of Louisiana that was reflected in La Harpe’s earlier correspondence. Spanish, French and American interests were all in play, as reflected by the beautiful and somewhat mysterious manuscript map of “Part of the Province of Louisiana, and part of West Florida and the Province of Texas” that is included in this exhibition.

The mapmaker, date and purpose of this map are speculative, but its title and content offer some clues. The map was clearly drawn as Spain grappled with the consequences of what it viewed as Napoleon’s illegal conveyance to the United States. It argues in graphic form for the identification of two important borders: that between Spanish West Florida and the United States, and that between Spanish Texas and the newly American Louisiana Territory.

The eastern portion of the map is quite detailed. The 31st parallel is acknowledged as the border between West Florida and the United States, as agreed in Pinckney’s Treaty. West Florida is prominently identified as “Territorio del Dominio de S. M. pertenece a la Florida” or Territory of the Dominion of His Majesty belonging to Florida, and the boundary corresponds to what the Spanish administered as a district of Baton Rouge within their Province of West Florida. The region to the north and east of the Mississippi is simply labeled “Territorio Americano” or American Territory. Notably, no Spanish or Native American settlements are identified in the American lands. A fort (“Fuerte Americano”) appears just within the territory east of the river. Construction of what came to be named Fort Adams commenced in 1798, as the formal survey of the 31st parallel was being made. It played an important role in 1802 as the site of a conference between Americans and the Choctaw tribe for the construction of what became the Natchez Trace. All of these elements in the map appear to be intended to argue that American claims were limited to above the 31st parallel.

To the west the map's subject turns to the border between Texas and Louisiana. The border line on the mapfollows the Sabine River north and then displays a prominent triangular diversion to the east of the river, with the settlement of Adais (Los Adaes) at the point. Los Adaes was settled in 1716 to offset French settlement in Natchitoches. Its first appearance on a map was in De L’Isle’s 1718 map of the course of the Mississippi. It was the colonial capital of Spanish Texas until 1770, when the capital was moved to San Antonio. A mix of Spaniards, French and Native Americans continued to live there as this map was drawn. Significantly, the only road marked on the map is the one from Los Adaes to San Antonio, reinforcing Spain’s claim to the settlement.

While the United States continued to assert that Louisiana extended all the way to the Rio Grande River, negotiations focused on the Sabine, which would place Texas within Spanish Mexico. Spain argued that the border was father east yet – following a small stream or Arroyo Hondo in modern day Louisiana. Under that interpretation, Los Adaes would be in Texas, even though it was on the east side of the Sabine. Both the United States and Spain sent troops to the area, but in 1806 the two commanders agreed that the property between the two lines would remain “neutral ground” until a diplomatic solution could be found. The Arroyo Hondo does not appear on this map, but the triangular area with Los Adeas at its point is squarely within the Neutral Ground. The deviation of the border east of the Sabine on this map might reflect a proposal to resolve the issue. If so, it was not successful. Spain and the United States broke off diplomatic relations in from October 1805 to October 1806, and it took until the Adams Onis Treaty in 1819 before the issue was finally resolved. In that treaty the border did not deviate east of the Sabine River.

From the Sabine border the map extends west as far as San Antonio. Most of the principal rivers in Texas, from the Sabine to the San Marcos, appear on the map, linked by the road. Other than the mouth of the Mississippi, however, the map does not show the connection of any of those rivers to the Gulf of Mexico. The description of Texas, with its emphasis on its rivers, may have been to highlight the value of the region for Spanish settlement, and as a buffer between the United States and the riches of Mexico.

The quality of the map’s execution, the expensive English paper on which it was drawn, and the large scale all suggest the map was made for a person of importance or influence. It may have been prepared for the Marques de Casa Calvo, a former Spanish military governor of Louisiana who was appointed a commissioner to assist in the retrocession to France. Between 1804 and 1806, even after the establishment of the American regime in Louisiana, he led a major expedition to explore, research and ultimately define a western border of Louisiana and the eastern border of Texas. Casa Calvo’s principal deputy described a sketch based on a Spanish chart that included boundary lines exactly as depicted here. Among Casa Calvo’s experts was the French engineer Nicolas de Finiels. Finiels delivered a detailed report to Luis de Onis, who subsequently negotiated the Adams Onis treaty. That report included discussions of both of the highlighted border areas drawn on this map. Indeed, this map may have been made by Finiels as an aid to discussing the issues with his superiors, including Casa Calvo or even Onis.

More scholarship may finally ascertain the author and precise date of this map. In the meantime, it stands as a unique artifact of a time of dramatic and historic change.

![ANONYMOUS [Nicolas de Finiels?] Plano de una parte de la Prov.a de la Luisiana; ... 1803](http://aradernyc.com/cdn/shop/products/Webcapture_8-9-2022_133119.jpg?v=1662674802&width=1445)