from: Maps

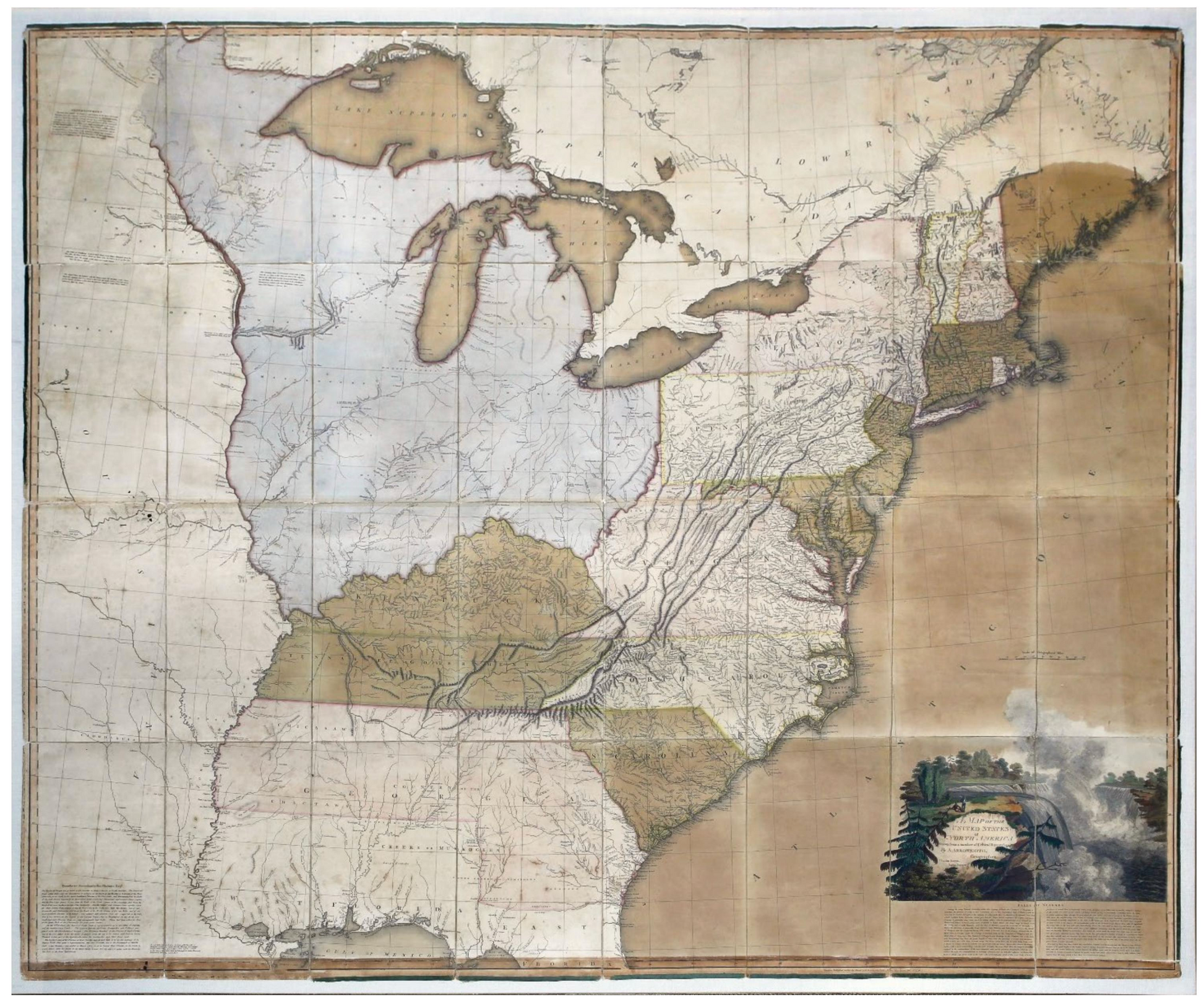

Aaron Arrowsmith. A Map of the United States of North America... 1796

Aaron Arrowsmith. A Map of the United States of North America... 1796

Couldn't load pickup availability

AARON ARROWSMITH (1750–1823)

A Map of the United States of North America, Drawn from a number of Critical Researches by A. Arrowsmith, Geographer

Engraved wall map with original hand color, mounted on cartographic linen

London: A. Arrowsmith, 1796. (First Edition, original issue: Stewart 79a)

Sheet size: 49 1/4” x 57”;

Frame size: 56” x 63”

FIRST EDITION, FIRST ISSUE. WITH MAGNIFICENT & PERFECT ORIGINAL COLOR

Arrowsmith’s map was the first English wall map to use the term “United States” to describe the newly independent colonies in North America, and demonstrated the difficulties facing cartographers seeking to identify the enormous concession of lands made by England in the Treaty of Paris.

It is often said that the Treaty of Paris in 1783 explicitly recognized the “United States” as a nation. It certainly had that effect, but the language in the treaty reflected a certain ambiguity about what that meant.

The three American representatives charged with negotiating the treaty were appointed by the Continental Congress, which was operating under the Articles of Confederation. The Constitution, of course, was not adopted until 1787. This presented the European powers with many opportunities to influence the outcome of peace negotiations, for good and bad. Also, to a large extent each of the colonies felt free to have its own foreign policy, making the task of the negotiators a difficult one. In the words of John Jay, peace was achieved “in spite of the malice of enemies, the finesse of allies and the mistakes of Congress.”

On the British side, the chief negotiator’s original commission charged him with negotiating with the thirteen “colonies or plantations, or any of them on any part or parts of them.” This proved inadequate, so some five months later his commission was revised to authorize him to negotiate with “the Thirteen United States of America, Viz: New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, the three lower Counties on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia in North America, a Peace, or a Truce with the said thirteen United States…” This precise language was used in the Treaty of Paris. It acknowledged that the thirteen former colonies were “united” but the treaty consistently used the plural to describe the states.

Whatever the definition of the “United States” the Treaty of Paris also represented a stunning concession of land by Great Britain, extending the new nation from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River. The treaty explicitly described the boundaries of the lands belonging to the states, but since the best information available was Mitchell’s 1755 map, the treaty necessarily created some ambiguities that challenged subsequent cartographers.

On such mapmaker was Aaron Arrowsmith. Arrowsmith was England’s preeminent wall map publisher, and the founder of a cartographic dynasty that continued for generations. His talents were in synthesis, using a variety of sources including the records of the Hudson’s Bay Company. His 1795 Map of the Interior of North America used such records to make the most useful map of the day about the topography of the American west; a later edition accompanied Lewis and Clark. But his 1796 Map of the United States of North America was intended to be a political map; an up to date map depicting the territory and boundaries of the new “United States.” It was the first English wall map to use that name.

Arrowsmith’s map is an aesthetic masterpiece, particularly with the extraordinary coloring displayed in this example – the best we have ever seen on this map. On the other hand, as the first state of a much-updated map it reflects some of the challenges created by the Treaty of Paris, and by subsequent events. One example is the northern boundary between the District of Maine and British Canada. The Treaty of Paris began its description of the boundary of the United States at “the Northwest Angle of Nova Scotia” which the treaty defined as being a point on the “highlands” at the end of a line going north from the head of the St. Croix River. Arrowsmith began his boundary line at what he called the “land’s hight” but made no reference to the northwest angle, and neither his engraver nor his colorist seemed confident on the actual location of the boundary. This uncertainty was understandable since it had never been surveyed. The actual location remained disputed (occasionally with the threat of violence) well into the 19th Century. The border dispute was finally resolved in the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1841.

In the South, the treaty established a border with West Florida at the 31st parallel. This corresponded to the border of West Florida established by the English in 1763 after the French and Indian War. This ignored the fact that the English expanded West Florida in 1764 by moving the border north to 32 degrees 22 minutes, which is presumably where it still was when the Revolution ended.

Spain was not a party to the Treaty of Paris, but the revolution was a global war, and it had claims to make as part of the settlement. In a separate treaty, to which the United States was not a party, Spain recovered Florida and West Florida from England, basically as a consolation prize for not receiving Gibraltar, its real goal in the war. However, the treaty between England and Spain did not define the northern border of West Florida. Spain asserted that the border was at 32 degrees 22 minutes as it had been set in 1764; the United States claimed that the 1763 border at the 31st parallel applied. This conflict between Spain and the United States was resolved in 1795 in Pinckney’s Treaty. Arrowsmith may not have gotten the news; certainly his colorist on this example did not. The border is clearly delineated in color at 32 degrees 22 minutes, granting Spain a far larger West Florida than it had recently agreed to accept. Subsequent states of the map properly locate the border at the 31st parallel, making this rare first state an example of the difficulties facing even the most talented mapmaker trying to capture the changing shape of North America.