Excerpt from 'Thomas Moran' Book published by The National Gallery of Art/Yale. Pages 319-321

"Posters" and Art Calendars

As advertising became more sophisticated, Moran's work was increasingly in demand for calendars, ink blotters, travel brochures, and other ephemera, and by the early 1890s his paintings were being reproduced on a large scale through chromolithography, letterpress, and eventually the new technique of offset lithography. These developments offered an entirely new way to promote his work, and Moran began selling copyright of existing images rather than painting new designs for reproduction. Although mechanical processes distanced the final product from the original creation, photographically reproduced images printed via letterpress were touted by publishers as respectable substitutes for original works of art, and they were well received by average Americans. As a result, such ventures were important to Moran's commercial career, his reputation as an artist, and indeed the status of reproductions as art.

In 1892 he returned to the Grand Canyon for the first time since his initial trip, with Powell in 1873. As part of the three-month trip, he traveled for the Santa Fe Railway, which had extended its line nearly to the canyon, and he produced a major painting, The Grand Canyon of the Colorado, for the company in exchange for the trip. The finished oil hung for a number of years at the El Tovar Hotel at the Canyon, and chromolithographs of it became an important advertising tool in the early years of the Santa Fe Railway as the company established its identity as one of the most innovative patrons of art in the West. Once the SFRR line actually reached the canyon in 1901, the railway began a program that enabled artists to visit the site in return for paintings that would adorn offices, hotel lobbies, and depots, and would appear in advertisements and calendars. To further encourage the visual promotion of this natural tourist attraction, "artists' excursions" were held in 1901 and again in 1910, and Moran participated in both.

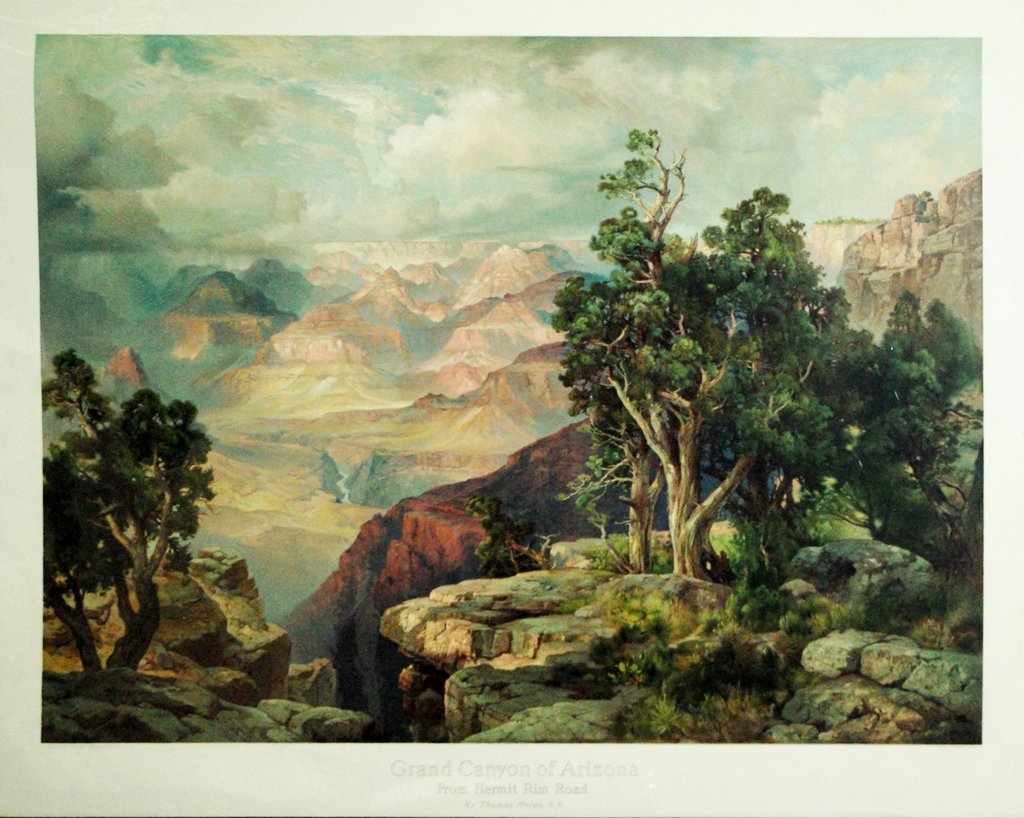

Recognized as an influential advocate for the area, Moran traveled via the SFRR to the Grand Canyon annually until about 1920 and was provided with lodging and a studio at the rimside El Tovar. He was consistently acknowledged in the company's tourist literature, and in 1912, twenty years after its first purchase of his art, the railroad bought another painting from which it printed 2,500 chromolithographs. This oil, The Grand Canyon from Hermit Rim Road, remains in the railroad's corporate collection, and the chromolithograph has become a valuable collector's item.

As chromolithographs were replaced by more efficient methods of reproduction, Moran enthusiastically sold copyrights of his work to emerging companies. This provided him the luxury of selling his work twice: each copyright brought an average of $500, and he could still ell the original oil painting. He was obviously thinking of such benefits during his 1892 trip when he wrote to his wife, ''Jackson and I are concocting a scheme for publication of six subjects of grand size of the Holy Cross, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Shasta, and two others. He says they sell well right along and would be a steady source of income to me. He says he has paid Bell about a thousand already in royalty on the Holy cross," Although the details remain unclear, a later letter from Jackson written from the Detroit Publishing Company suggests that he arranged for the photography of Moran's work and acted as the broker to the publisher. The final outcome is uncertain, but correspondence as late as 1901 indicates it was an ongoing project.

Similar to the reproductions Moran and Jackson planned were art calendars, a phenomenon in early twentieth-century printing and advertising. Moran's artworks were among the first to be reproduced and distributed in this way. Although many companies quickly replicated the idea, it was conceived in 1889 by Thomas D. Murphy and his friend and fellow newspaper editor Edmund B. Osborne in Red Oak, Iowa, as a way to supplement their newspaper business. The calendars, adorned with a fine art reproduction and accompanied by advertising copy for local businesses, were given to clients as promotional gifts. To make his products distinctive, Murphy commissioned original art and purchased copyrights to paintings, and he quickly developed a unique industry that featured Moran's work prominently.

Murphy's calendars were produced to high specifications, and the company took great pride in its relationship with artists and its collection of original oils. Between 1910 and 1926 Moran sold the firm nearly sixty copyrights, and Murphy illustrated at least two of his own books with Moran's works. He boasted in 1925 that "the pictures of [H.J.] Dobson and Moran are about the only ones that have not waned in popularity during the past fifteen years," and he took some pride in being a factor in that continuing popularity.

In 1894-1895 Murphy's partner, Edmund Osborne, left Red Oak to establish his own art calendar company in Allwood, New Jersey. Osborne and Company also energetically promoted Moran's art, primarily through large-scale reproductions as well as calendars. In later years Murphy and Osborne rejoined forces to form the American Colortype Company, and it, along with Osborne and Company and JII / Sales Associates, heir to the Murphy Company, continued to publish Moran's work even after the artist's death. In 1936 Osborne and Company produced a special anniversary calendar for the New York Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank, complete with a short biography of Moran and twelve reproductions of his paintings. Moran's daughter Ruth wrote the company that "it would have pleased my father, Thomas Moran, to observe with what fidelity modern machinery and skill can now reproduce these miniature facsimiles of the artist's work. And it is also a pleasure to know that the public appreciates these reproductions."

Too often overshadowed by his painting in art historical literature, commercial work was a primary means of economic support for Moran through most of his life. In the artist's own opinion and in that of many of his contemporaries, it comprised an important vehicle for his talent and vision. Commissions for illustrations provided him occasins for travel and artistic inspiration, and in many cases the resulting wood engravings formed the basis for more monumental work.

Even after he left illustration, Moran continued to focus on reproducing his art through the most modern means available. His commercial art brought him into contact with some of the most influential individuals and corporations of his time, which in turn contributed to his success as a fine artist in the grand tradition.

The marginalization of Moran' career in reproduction is largely a product of twentieth-century attitude toward aesthetic hierarchies and not something to which the artist himself ascribed. Indeed the period of his most prolific activity was precisely when illustration enjoyed acceptance as an art form. It should be remembered that Thomas Moran's commercial work, which extended over seven decades, profoundly influenced Americans' evolving conception of this country and its unique landscape. This aspect of his diverse career stands out as a major component of his development and his profound achievement as an American artist.

|

|