from: Poiteau & Turpin Superb Botanical Drawings including varieties from the West Indies

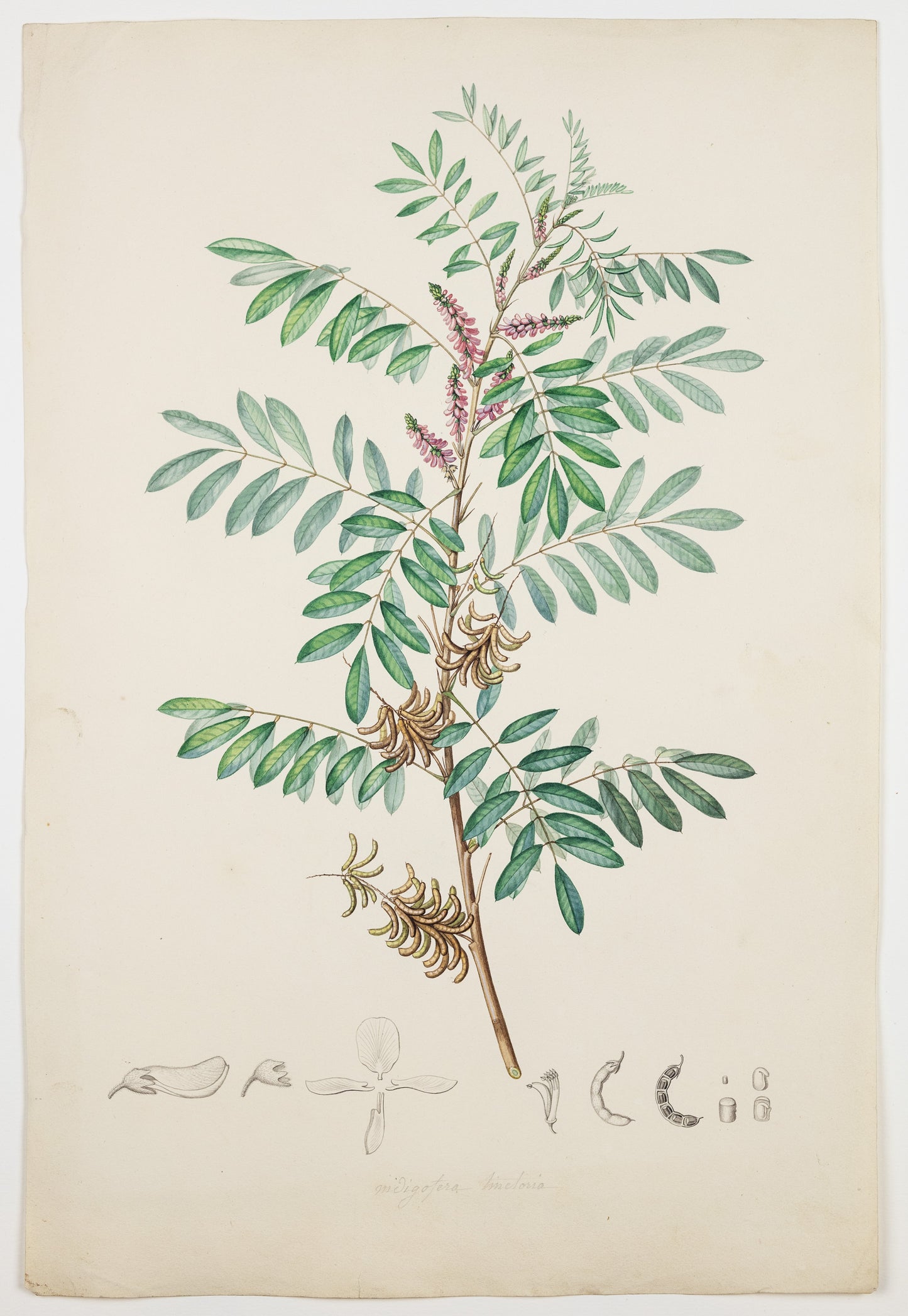

PIERRE JEAN FRANÇOIS TURPIN (FRENCH, 1775–1840). Wild Indigo. 1808–1827.

PIERRE JEAN FRANÇOIS TURPIN (FRENCH, 1775–1840). Wild Indigo. 1808–1827.

Couldn't load pickup availability

PIERRE JEAN FRANÇOIS TURPIN (FRENCH, 1775–1840)

“Indigofera [Anil]”

[today known as Indigofera suffruticosa, Wild indigo, also known as indigo, Guatamala indigo, añil, añil de pasto, and ti cafe]

Preparatory drawing for F.R. Tussac, Flore des Antilles, ou histoire générale botanique, rurale et economique des végétaux indigènes des Antilles.

Paris: chez l’auteur, F. Schoell et Hautel, 1808–1827. Vol. 2, Pl. 9

Watercolor and pencil on paper

Inscribed “Indigofera tinctoria”

Paper size: 18 x 12 in.

Turpin’s original drawing is labeled “Indigofera tinctoria,” Old World indigo, but later re-titled this image, when it appeared in Flore des Antilles, as “Indigofera anil Indigofere Franc.” This correction to the title, making the distinction of the species to be the indigo grown specifically in the French West Indies, provides fascinating insight to the New World trade wars between the Spanish, French, and British.

Due to its vibrant deep blue color, excellent color fastness to light, and the wide range of colors obtained by combining it with other natural dyes, indigo has been referred to as “the king of dyes.” No other dye plants have held such a prominent place in as many civilizations.

Lamarck referred to this plant as “indigotier franc” or “I. ail” in his Encyclopedie Methodique (1789). In Flore des Antilles, Tussac suggested a name change, emphasizing that “indigotier” refers to someone who manages an indigo manufactory. Therefore, he proposed a new name: Indigofera, which later became the official genus.

David Rembert Jr. concisely explained the role of indigo in the New World during the 18th and early 19th centuries:

“By the 18th century, the English and French had begun indigo cultivation in the New World as the trade in indigo from India rapidly declined. The decline in Indian exports was due to various factors. Initially, the procedures in India became lax, leading to a decrease in the quality of their produce. Britain turned first to her West Indian territories, such as Jamaica, and then to her colonies in North America, particularly South Carolina, as new sources for dyes. Meanwhile, the Spanish and French expanded their efforts in the West Indies and Central America.”

—David H. Rembert Jr., Economic Botany, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Apr.–Jun., 1979), p. 129

The indigo trade was driven by three species: I. arrecta, I. tinctoria, and I. suffruticosa. The first two were Old World varieties, and the third was a New World species. In the 16th century, the Portuguese brought I. suffruticosa to India through the trade routes between Africa and India. Before this, the only indigo in Europe was I. tinctoria, sourced within Europe. The introduction of indigo from India had a profound impact and led to sanctions on sources from outside of Europe; the powerful guilds that controlled the use and trade of indigo even issued death threats. Eventually, the Dutch monopolized the trade through the Dutch East India Company.

Indigo played a significant role in North American colonial trade, as South Carolina indigo made up 35% of the annual exports to England. Regarding the specific variety, Indigofera carolinana, it is unknown if it was a variety of I. tinctoria or I. suffruticosa. Both were being grown in South Carolina when this variant emerged. In the West Indies, the English focused on sugar and coffee exports, leaving the French to specialize in indigo exports from their West Indian colonies.

Despite the overwhelming demand for indigo, it was not easy to manufacture. The freshly cut plants were immersed in large vats lined with bricks. After fermentation, the plants were trampled in the tanks by laborers, causing the dye to settle at the bottom to form small cakes that were later dried. This labor-intensive process was both costly and presented tremendous health hazards for workers. Thus, indigo remained an expensive commodity until manufacturing techniques advanced.

Appeared in F.R. Tussac. Flore des Antilles, ou histoire générale botanique, rurale et economique des végétaux indigènes des Antilles. Paris: chez l’auteur, F. Schoell et Hautel, 1808-1827 Vol. 2 Pl. 9