from: All Birds/Ornithology

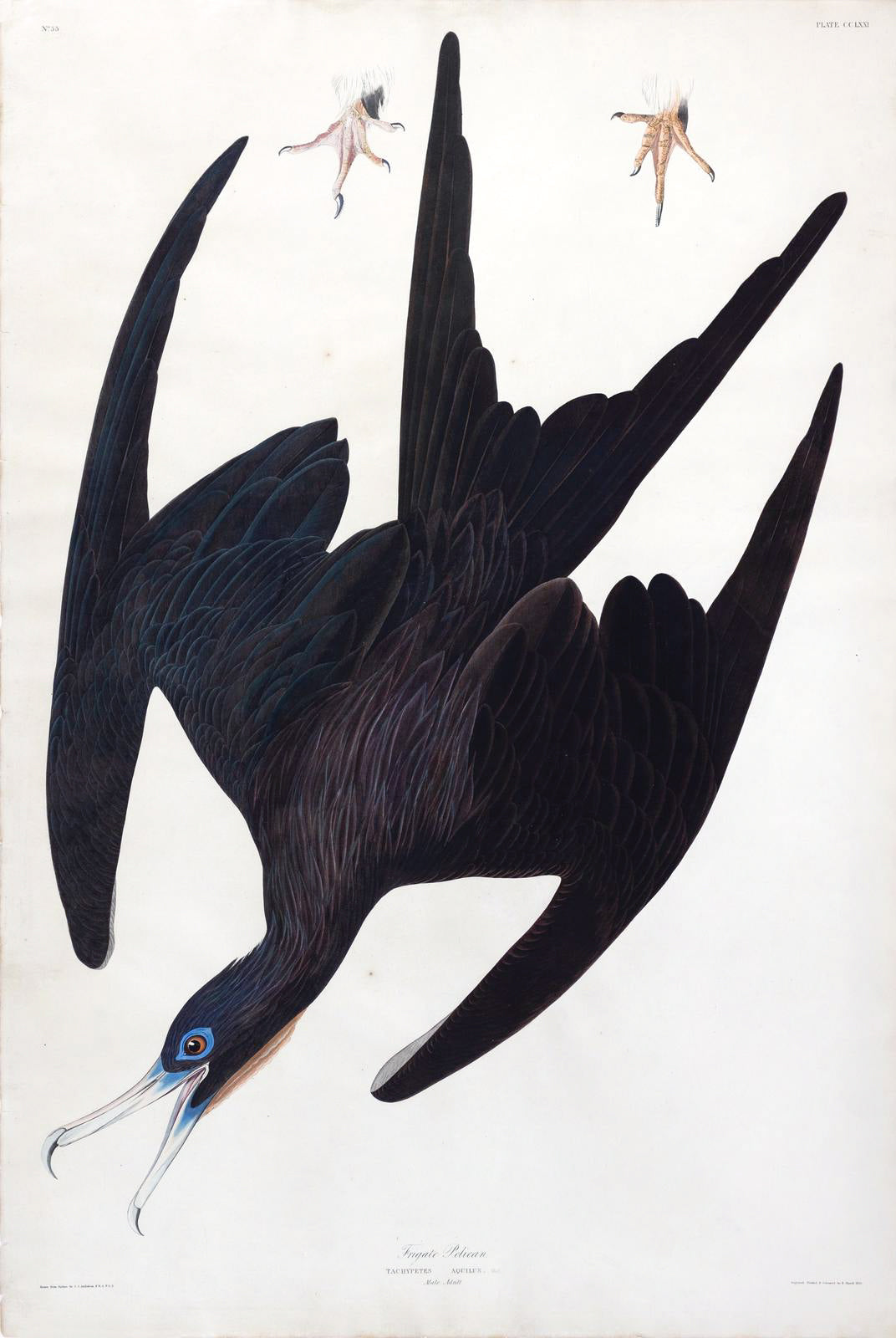

John James Audubon (1785-1851), Aquatint Plate CCLXXI, Frigate Pelican

John James Audubon (1785-1851), Aquatint Plate CCLXXI, Frigate Pelican

Couldn't load pickup availability

AUDUBON, John James (1785 - 1851).

Frigate Pelican, Plate CCLXXI (271).

Aquatint engraving with original hand color.

London: Robert Havell, 1827-1838.

38 5/8" x 26 1/4" sheet.

This image has been a favorite for the great decorators of the 1970s and 1980s.

"The Frigate Pelicans may be said to be as gregarious as our Vultures. You see them in small or large flocks, according to circumstances. Like our Vultures, they spend the greater part of the day on wing, searching for food; and like them also, when gorged or roosting, they collect in large flocks, either to fan themselves or to sleep close together. They are equally lazy, tyrannical, and rapacious, domineering over birds weaker than themselves, and devouring the young of every species, whenever an opportunity offers, in the absence of the parents; in a word, they are most truly Marine Vultures." - (Audubon's Ornithological Biography, 1831).

John James Audubon is without rival as the most celebrated American natural history artist. Audubon devoted his life to realizing his dream of identifying and depicting the birds of North America, and his work has had profound cultural and historical significance. In the second decade of the 19th century, he set out to travel throughout the wilderness of the United States, drawing every notable species of native bird. His remarkable ambition and artistic talent culminated in the publication of the monumental Birds of America in 1827-38, a series of 435 aquatints that have only grown in fame since the time of their first appearance. This work established Audubon as an early American artist who could attract European attention, and for many, he personified New World culture and its emerging independent existence.

Audubon was born in Haiti, the illegitimate Creole son of a French sea merchant and a local chambermaid. He was raised in France until 1803, when his father sent him to the United States to avoid being drafted into the Napoleonic wars. There he started what proved to be a long run of unsuccessful schemes. He tried to run a lead mine in Pennsylvania. It folded. After marrying, he opened up a store in Louisville and it, too, went under. He started a steamboat line, and it led him into bankruptcy. By then he was 35 and, he admitted to his wife, a failure.

But throughout his life he nourished a passion for the study and illustration of bird life. At the time, marketing was not as unlikely an endeavor for Audubon as it might seem today. It was a respectable, if somewhat chancy, business, and natural history was a popular subject; in fact, Audubon faced considerable competition. He had little formal training in art and even less in ornithology, but what he lacked in experience he made up for in braggadocio. He pursued his birds with an unusual passion for accuracy and painterly beauty, a fervor caused as much by desperation as by scientific and aesthetic high-mindedness. For years he tracked his subjects to the known edges of the country; the journals he kept along the way are a literary achievement in themselves. By his death in 1851, he had completed 584 individual studies, 435 of which appeared in The Birds of America.