from: All Fish & Reptiles

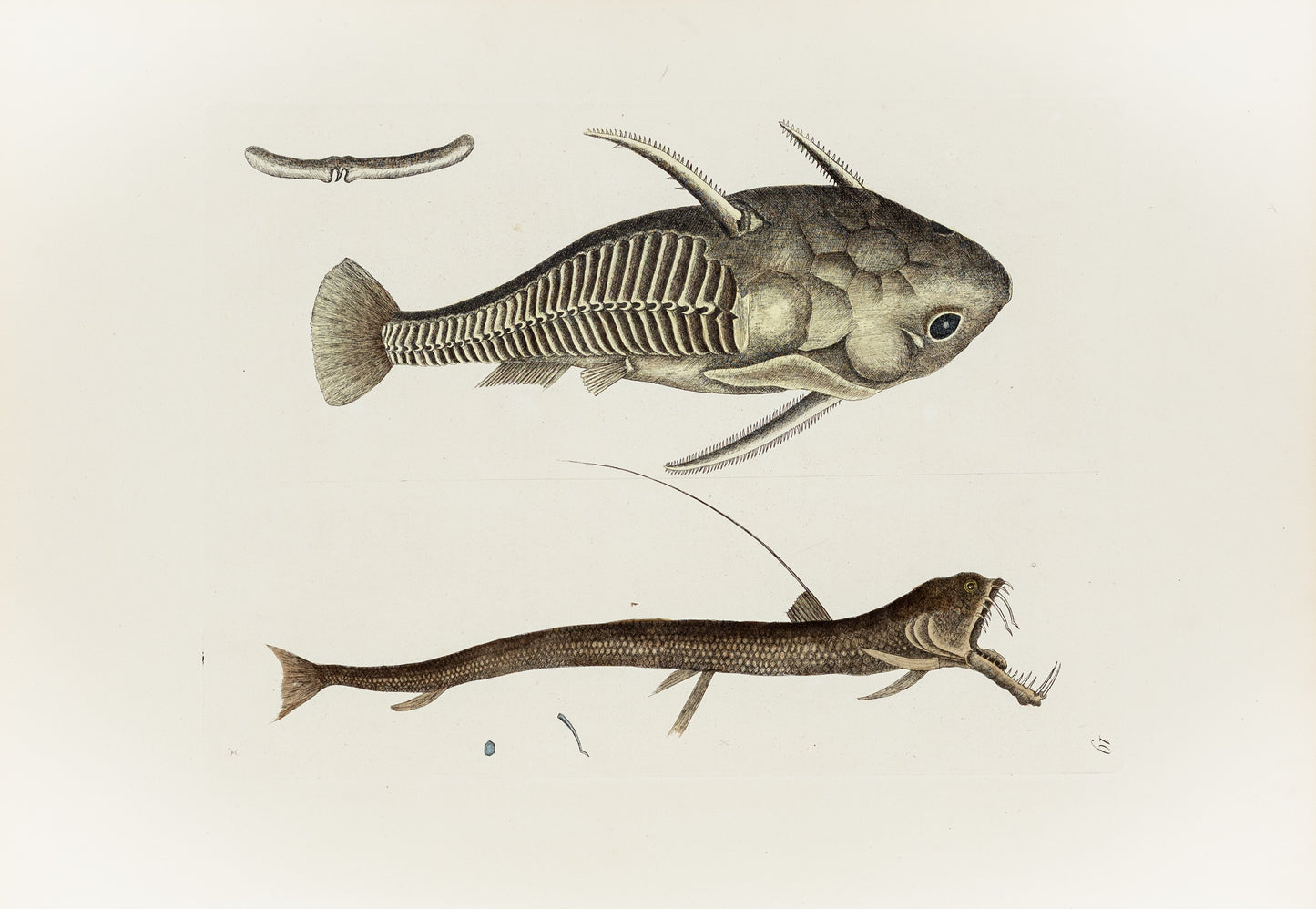

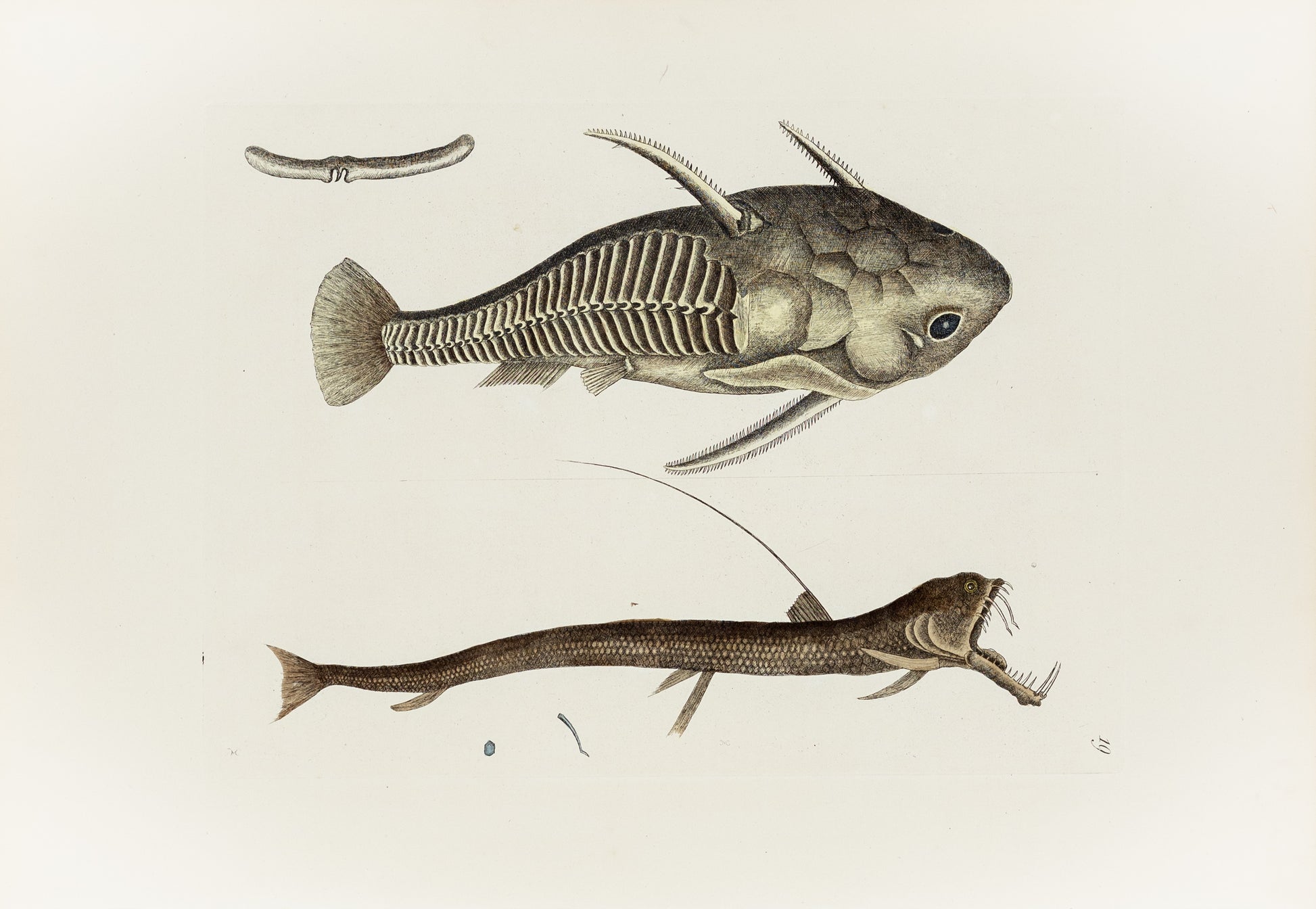

Catesby, Mark. Appendix Pl. 19, The Viper-Mouth

Catesby, Mark. Appendix Pl. 19, The Viper-Mouth

Couldn't load pickup availability

Mark Catesby

The Viper-Mouth, Appendix Pl. 19

Etching with hand color

14" x 19" sheet

From the Appendix (Part 11) to Catesby's Natural History of Carolina, Florida & the Bahama Islands

London: 1747 - 1771

Currently known as the viperfish, Chauliodus sloani and the spiny catfish, Acanthodoras cataphractus*, Catesby described these subjects as follows:

VIPERA MARINA

The VIPER-MOUTH.

THIS Fish is eighteen inches in length. The fins six in number, viz. one on the fore-part of the back, which terminates in a stiff hair or bristle four inches long; a pair of sharp-pointed fins grow under the gullet, and another pair under the middle of the belly; with a single one behind the anus. The number of teeth in each jaw was unequal; the upper-jaw had eight teeth, the two second being much longer than the other fix, each having an angular bending near their ends. The two fore-teeth of the under-jaw are almost: of equal length with those two of the upper-jaw just mentioned, but without those bendings, These four large teeth being too long to be contained within the mouth, are, at the shutting it, excluded; those of the upper-jaw lying close to the under-one, and those of the under-jaw lying close to the crown of the head. It is without scales. In the state it was sent me, it was of a brown colour, resembling that of the common Viper; but when just taken out of the Water they are, as I am told, of a green colour, but marked all over with small hexangular divisions. This odd Fish was sent me from Gibraltar, in the Harbour of which place it was taken, and is now preserved in the celebrated of Repository of Sir HANS SLOANE.

Cataphractus Americanus,

THIS Fish was ten inches long, and about four broad. The whole upper-part of the body was covered with bone. The eyes were large, the mouth was small and void of teeth. On the back stood, reclining towards the tail, a flat pointed bone three inches long, and serrated on the upper edge, which being fixed in a socket, the Fish could erect and depress at pleasure. Under each gill was placed another such-like bone, except that both edges were serrated, the teeth on one side standing retrograde to the teeth of the other. The fore-part of the body and head was covered intirely with bone, marked with many regular lines, forming octagons, pentagons, &c. The hind-part of the body was also covered with bone, but in a different manner, viz. with thin narrow plates of bone extending lengthways from the back to the belly, and lapping over one another. Each fide of this Fish had about thirty of these bones, which gradually diminished in size toward the tail; the middle of every one of these bones had a flat sharp point, like that of a lancet, which standing horizontally, and close to one another, formed an even line on each fide. On the hind-part of the back, in the place of a fin, for about half its length, extended a ridge of a cartilaginous substance, ending at its tail. The belly only was membranous, and void of bone.

It had five fins, a very small one under each of the gills, one on each fide of the abdomen, and a single one near the tail. This Fish being one of those called leather-mouthed, and having no teeth for defence. Nature seems to have compensated that deficiency by giving him weapons and armour in a very extraordinary manner. It was taken on the coast of New England and is deposited in the Musaeum of Sir HANS SLOANE.

Mark Catesby (1683 – 1749)

Facts regarding Catesby’s early years are scant. It is known that he was born in the ancient market town of Sudbury, England to a father who was a legal practitioner and mayor of Sudbury and to a mother from an old Essex family. It seems that he received an understanding of Latin and French and was familiar with the eminent naturalist Reverend John Ray. Following his father’s death, he was endowed with the means to pursue his interest in the natural history of North America.

Catesby arrived in Virginia in 1712 as the guest of his sister and her husband, Dr. William Cocke, an aid the Governor of the colony. Soon he was acquainted with the well-connected William Byrd, a Fellow of the Royal Society whose diary contains passages discussing Catesby’s strong curiosity with all things relating to North America.

This included plants native to the fields and woods of Virginia through which Catesby traveled, collecting examples of botanical specimens unfamiliar in England, which he illustrated and sent back to his uncle, Nicholas Jekyll and the apothecary and botanist, Samuel Dale.

Catesby’s first trip to the New World was extensive and included a visit to Jamaica. Although he felt that his approach to a larger understanding of its natural history was lacking in structure, his experience would inform his future expeditions.

Following his return to London in 1719 Catesby resolved to return to the colonies and gather additional information for his illustrated Natural History... He gained the financial support of members of the local scientific community, many of who were members of the Royal Society keen to send a naturalist to Carolina who could provide an accurate account of its resources. Among those who belonged to the Royal Society was William Sherard, who after examining Catesby’s drawings, was key in advancing the project. With further backing by Sir Hans Sloane, court physician and naturalist whose collection would form the basis for The British Museum, Catesby sailed to Carolina in 1722.

Catesby’s four years of travels following his second arrival in North America brought him throughout South Carolina, parts of Georgia, and the Bahamas. He was

intent on visiting the same location at different times throughout the year in order to observe his subjects as they developed. In addition to gathering botanical specimens of potential horticultural importance, he also acquired birds and other creatures.

Catesby’s patrons in London were eager to receive examples of the varieties of plants and animals he encountered but collecting, packaging, and sending them back to England served as a distraction to his intended Natural History... Nevertheless, he continued to observe, paint, and write descriptions of the previously un-investigated wildlife he encountered on the shores and in the swamps, woods, and fields of the middle American colonies.

Catesby returned to England from his final voyage to America in 1726 and spent the next seventeen years preparing his Natural History... He envisioned his work containing colored plates reproducing his studies from nature in a substantial, folio-sized format, an achievement nearly unprecedented in earlier natural history publications. Catesby arranged for financing in the form of an interest-free loan from the Quaker Peter Collinson, a fellow of the Royal Society. Nevertheless, the cost of paying professionals to prepare his delineations on copper plates for printing was too great. To this end, with the assistance of Joseph Goupy (1689–1769), a French artist living in London, he taught himself to etch. In addition to producing nearly all of the plates for his publication, Catesby closely supervised the coloring of the engravings, either painting the impressions himself or closely overseeing the work to insure its fidelity to his preparatory work. To further finance the project Catesby sold subscriptions, offering his book in sections of 20 plates to be published every four months.

The first volume of Natural History of Carolina, Florida & the Bahama Islands, containing one hundred plates, was completed in 1731 and no doubt facilitated his election as a fellow of the Royal Society in February, 1733. The second volume, also containing one hundred plates, was finished in 1743 and was supplemented with twenty plates based on information sent to Catesby by John Bartram and others in in America appeared in 1746–1747. Of the approximately 180 - 200 copies of the first edition produced, roughly 80 copies remain complete and accounted for and there are an unknown number in private collections. A second edition was issued by George Edwards in 1754 and a third edition, published by Benjamin White, in 1771 who continued to print examples of the plates until at least 1816. As early as 1749 editions were produced for the European market with translations of the text in German, Latin, and Dutch. In these the plates for the first volume and appendix were re-etched by Johann Michael Seligmann and the plates for the second volume re-etched by Nicolaus Friedrich Eisenberger and Georg Lichtensteger.

Catesby’s tenacity resulted in a sweeping and compelling study of American plants, animals, and marine life native to little documented lands in which he strove to assign scientific nomenclature to his subjects. Indeed, Linnaeus, in his 1758 Systema Naturae, made use of much information brought to light by Catesby using it as the foundation of his system of binomial nomenclature for American species.

Throughout the production of his Natural History…Catesby lived in London with his Elizabeth Rowland with whom he had four children and married in 1747, before his death in 1749.

*From James L. Reveal’s Identification of the plants and animals illustrated by Mark Catesby for The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama islands in the appendix of The Curious Mr. Catesby, University of Georgia Press.