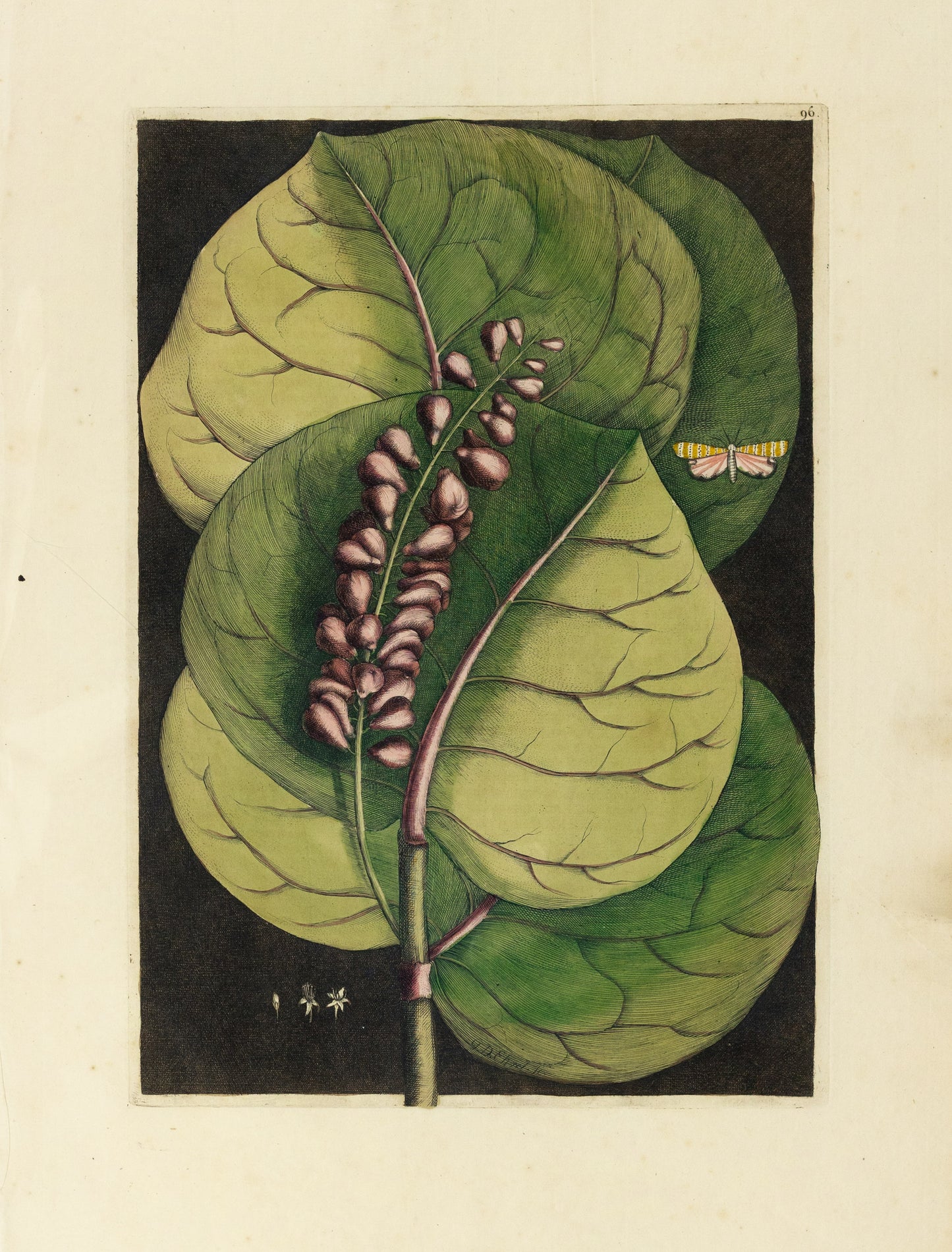

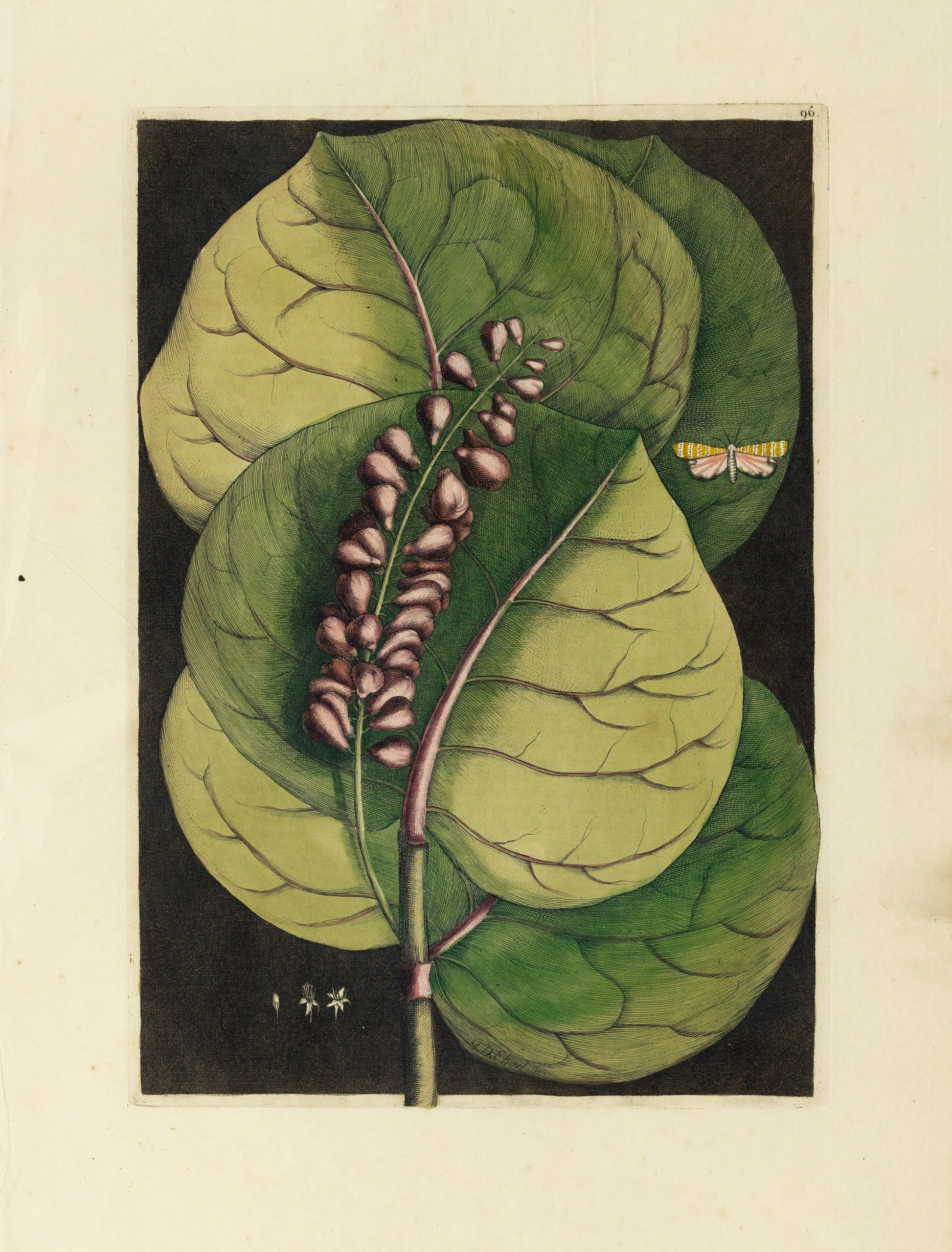

Catesby, Mark. Vol.II, Tab. 96, The Mangrove Grape-Tree, moth

Catesby, Mark. Vol.II, Tab. 96, The Mangrove Grape-Tree, moth

Couldn't load pickup availability

Etched by Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708 - 1770).

Etching with hand color, paper dimensions: approximately 14 x 19 inches

From Volume II, Part 10 of Catesby's Natural History of Carolina, Florida & the Bahama Islands

London: 1743 - 1771

Currently known as the ornate moth, Utetheisa bella* and sea-grape, Catesby described these subjects as follows:

PRUNUS maritima racemosa, folio rotundo glabro; fructu minore purpureo. Hist. Jam. Vol. II. p. 129

The MANGROVE GRAPE TREE.

The Trunks of these Trees are frequently two Feet thick, and seldom aspire above the Height of twenty or twenty-five Feet, the Bark is smooth, and of a brown Colour, the Leaves are set alternately, they are thick, broad, and almost round; and are eight, and some ten Inches Diameter: their middle Ribs are large and of a purple Colour, as are the smaller Veins; below the Pedicles of the Leaves, the Stalks are surrounded with a thin Purple Skin, or Membrane, an Inch in Width. The Flower-Stalks are usually ten Inches long, thick, succulent, and spongy, and rise at the Pedicles of the Leaves, usually standing upright, these Stalks except about three Inches of their lower Parts are thick set to the End; with small pentapetalous, greenish white Flowers, with yellow Stamina: These Flowers are succeeded by Pear shaped Fruit, about the Bigness of Cherries, resembling them also in the Consistence of their Pulp, and smooth Skin, but are of a purple Colour, inclosing a roundish Shell, thinner than that of a Filbert, and pointed at one End, within which lies the Kernel, of a singular and pretty Form, being flat at one End, and conic at the other, divided by three deep Furrows. This Fruit has a refreshing agreeable Taste, and is efteem'd very wholesome, but if the Stone be kept long in the Mouth, it is violently astringent: I never saw any but what grew near the Sea. They are plentiful on many of the Bahama IsIands, and in many other Countries between the Tropicks, but are no where to be found North or South of them: The Flower-stalk when the Fruit approaches to Ripeness, is shrunk, and much less than when the Blossoms were on it.

Dampier says the Wood of this Tree makes a strong Fire, therefore used by the Privateers to harden the Steels of their Guns, when faulty.

PHALAENA Caroliniana, minor; fulva, maculis nigris alba linea, pulchre aspersis. Pet. Gaz. Nat. Tab. III. Fig. 2.

This Moth has a dusky white Body, with a few black Spots near the Head; the two upper Wings are yellow, each of which is crossed by six while lines, spotted with black; the two under Wings are red, with their lower Parts verged with black. These Moths are found in Carolina.

Mark Catesby (1683 – 1749)

Facts regarding Catesby’s early years are scant. It is known that he was born in the ancient market town of Sudbury, England to a father who was a legal practitioner and mayor of Sudbury and to a mother from an old Essex family. It seems that he received an understanding of Latin and French and was familiar with the eminent naturalist Reverend John Ray. Following his father’s death, he was endowed with the means to pursue his interest in the natural history of North America.

Catesby arrived in Virginia in 1712 as the guest of his sister and her husband, Dr. William Cocke, an aid the Governor of the colony. Soon he was acquainted with the well-connected William Byrd, a Fellow of the Royal Society whose diary contains passages discussing Catesby’s strong curiosity with all things relating to North America.

This included plants native to the fields and woods of Virginia through which Catesby traveled, collecting examples of botanical specimens unfamiliar in England, which he illustrated and sent back to his uncle, Nicholas Jekyll and the apothecary and botanist, Samuel Dale.

Catesby’s first trip to the New World was extensive and included a visit to Jamaica. Although he felt that his approach to a larger understanding of its natural history was lacking in structure, his experience would inform his future expeditions.

Following his return to London in 1719 Catesby resolved to return to the colonies and gather additional information for his illustrated Natural History... He gained the financial support of members of the local scientific community, many of who were members of the Royal Society keen to send a naturalist to Carolina who could provide an accurate account of its resources. Among those who belonged to the Royal Society was William Sherard, who after examining Catesby’s drawings, was key in advancing the project. With further backing by Sir Hans Sloane, court physician and naturalist whose collection would form the basis for The British Museum, Catesby sailed to Carolina in 1722.

Catesby’s four years of travels following his second arrival in North America brought him throughout South Carolina, parts of Georgia, and the Bahamas. He was

intent on visiting the same location at different times throughout the year in order to observe his subjects as they developed. In addition to gathering botanical specimens of potential horticultural importance, he also acquired birds and other creatures.

Catesby’s patrons in London were eager to receive examples of the varieties of plants and animals he encountered but collecting, packaging, and sending them back to England served as a distraction to his intended Natural History... Nevertheless, he continued to observe, paint, and write descriptions of the previously un-investigated wildlife he encountered on the shores and in the swamps, woods, and fields of the middle American colonies.

Catesby returned to England from his final voyage to America in 1726 and spent the next seventeen years preparing his Natural History... He envisioned his work containing colored plates reproducing his studies from nature in a substantial, folio-sized format, an achievement nearly unprecedented in earlier natural history publications. Catesby arranged for financing in the form of an interest-free loan from the Quaker Peter Collinson, a fellow of the Royal Society. Nevertheless, the cost of paying professionals to prepare his delineations on copper plates for printing was too great. To this end, with the assistance of Joseph Goupy (1689–1769), a French artist living in London, he taught himself to etch. In addition to producing nearly all of the plates for his publication, Catesby closely supervised the coloring of the engravings, either painting the impressions himself or closely overseeing the work to insure its fidelity to his preparatory work. To further finance the project Catesby sold subscriptions, offering his book in sections of 20 plates to be published every four months.

The first volume of Natural History of Carolina, Florida & the Bahama Islands, containing one hundred plates, was completed in 1731 and no doubt facilitated his election as a fellow of the Royal Society in February, 1733. The second volume, also containing one hundred plates, was finished in 1743 and was supplemented with twenty plates based on information sent to Catesby by John Bartram and others in in America appeared in 1746–1747. Of the approximately 180 - 200 copies of the first edition produced, roughly 80 copies remain complete and accounted for and there are an unknown number in private collections. A second edition was issued by George Edwards in 1754 and a third edition, published by Benjamin White, in 1771 who continued to print examples of the plates until at least 1816. As early as 1749 editions were produced for the European market with translations of the text in German, Latin, and Dutch. In these the plates for the first volume and appendix were re-etched by Johann Michael Seligmann and the plates for the second volume re-etched by Nicolaus Friedrich Eisenberger and Georg Lichtensteger.

Catesby’s tenacity resulted in a sweeping and compelling study of American plants, animals, and marine life native to little documented lands in which he strove to assign scientific nomenclature to his subjects. Indeed, Linnaeus, in his 1758 Systema Naturae, made use of much information brought to light by Catesby using it as the foundation of his system of binomial nomenclature for American species.

Throughout the production of his Natural History…Catesby lived in London with his Elizabeth Rowland with whom he had four children and married in 1747, before his death in 1749.

*From James L. Reveal’s Identification of the plants and animals illustrated by Mark Catesby for The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama islands in the appendix of The Curious Mr. Catesby, University of Georgia Press.